< Return to Trans Guernsey

THE TRANS TEAM AT LIBERATE ARE WORKING CLOSELY WITH HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS AT GUERNSEYS HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICE DEPARTMENT TO ADVANCE THE SYSTEM OF CARE FOR TRANS PATIENTS.

Gender dysphoria is a condition where a person experiences discomfort or distress because there is a mismatch between their biological sex and gender identity. Biological sex is assigned at birth, depending on the appearance of the genitals. Gender identity is the gender that a person “identifies” with or feels themselves to be.

While biological sex and gender identity are the same for most people, this is not the case for everyone. For example, some people may have male-typical anatomy but identify themselves as a woman, while others may not feel they are definitively either male or female.

This mismatch between sex and gender identity can lead to distressing and uncomfortable feelings that are called gender dysphoria. Gender dysphoria is a recognised medical condition, for which treatment is sometimes appropriate. It is not a mental illness.

The condition is also sometimes known as gender identity disorder (GID), gender incongruence or transgenderism.

Some people with gender dysphoria have a strong and persistent desire to live according to their gender identity, rather than their biological sex. These people are sometimes called transsexual or trans people. Some trans people have treatment to make their physical appearance more consistent with their gender identity.

Gender dysphoria is not the same as transvestism or cross-dressing and is not related to sexual orientation. People with the condition may identify as straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual or asexual, and this may change with treatment.

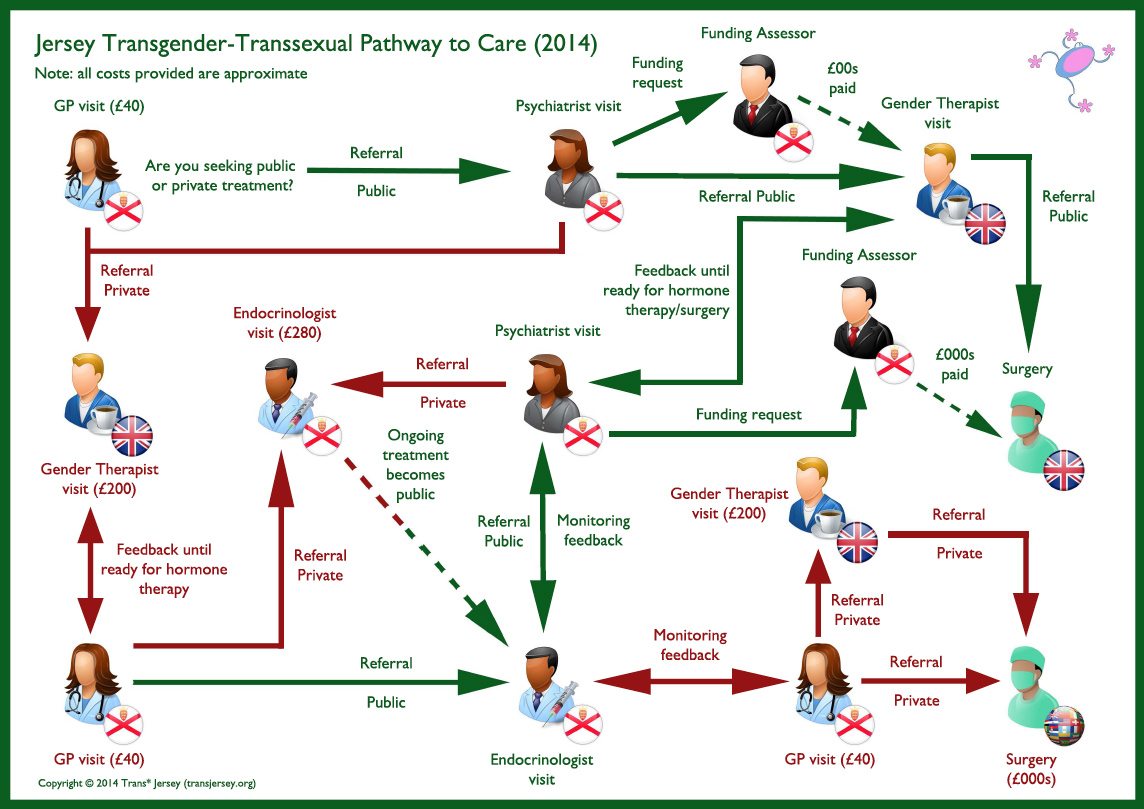

Guernsey are working towards an updated care pathway which will be similar to that which is used in Jersey. The diagram below explains the process of care for transgender people in Jersey.

Causes of gender dysphoria

The causes of gender dysphoria are not yet fully understood. Gender dysphoria was traditionally thought to be a psychiatric condition, with its causes believed to originate in the mind. However, more recent studies have suggested that gender dysphoria is biological and caused by the development of gender identity before birth.

The condition is not a mental illness.

Typical gender development

Much of the development that determines your gender identity – the gender you believe yourself to be – happens in the womb (uterus).

Your biological sex is determined by chromosomes. Chromosomes are the parts of a cell that contain genes (units of genetic material that determine your characteristics). You have two sex chromosomes: one from your mother and one from your father.

During early pregnancy, all unborn babies are female, because only the female sex chromosome (the X chromosome), which is inherited from the mother, is active. At the eighth week of gestation, the sex chromosome that is inherited from the father becomes active; this can either be an X chromosome (female) or a Y chromosome (male).

If the sex chromosome that is inherited from the father is X, the unborn baby (foetus) will continue to develop as female with a surge of female hormones. The female hormones work in harmony on the brain, reproductive organs and genitals, so that the sex and gender are both female.

If the sex chromosome that is inherited from the father is Y, the foetus will develop as biologically male. The Y chromosome causes a surge of testosterone and other male hormones, which starts the development of male characteristics, such as testes. The testosterone and other hormones work in harmony on the brain, reproductive organs and genitals, so that the sex and gender are both male.

Therefore, in most cases, a female baby has XX chromosomes and a male baby has XY chromosomes, and there is no mismatch between biological sex and gender identity.

Changes to gender development

Gender development is complex, and there are many possible variations that cause a mismatch between a person’s biological sex and their gender identity.

Hormonal problems

Occasionally, the hormones that trigger the development of sex and gender may not work properly on the brain, reproductive organs and genitals, causing differences between them. For example, the biological sex (as determined physically by the reproductive organs and genitals) could be male, while the gender identity (as determined by the brain) could be female.

This may be caused by additional hormones in the mother’s system (possibly as a result of taking medication), or by the foetus’s insensitivity to the hormones, known as androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS). When this happens, gender dysphoria may be caused by hormones not working properly in the womb.

Other rare conditions, such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), and intersex conditions may also lead to gender dysphoria.

In CAH, the adrenal glands (two small, triangular-shaped glands located above the kidneys) in a female foetus cause a high level of male hormones to be produced. This causes the genitals to become more male in appearance and, in some cases, the baby may be thought to be biologically male when she is born.

Intersex conditions cause babies to be born with the genitalia of both sexes (or ambiguous genitalia). In such cases, it used to be recommended that the child’s parents should choose which gender to bring up their child as. However, it’s now considered better to wait until the child can choose their own gender identity before any surgery is carried out.

Symptoms of gender dysphoria

There are no physical symptoms of gender dysphoria, but people with the condition may experience and display a range of feelings and behaviours.

In many cases, a person with gender dysphoria will begin to feel that there is a mismatch between their biological sex and gender identity during early childhood. For others, this may not happen until adulthood.

Gender dysphoria in children

Gender dysphoria behaviours in children can include:

- insisting that they are the other sex, or not feeling like or identifying with the perceived sex.

- disliking or refusing to wear clothes that are typically worn by their sex and wanting to wear clothes that are typically worn by the opposite sex

- disliking or refusing to take part in activities and games that are typically associated with their sex, and wanting to take part in activities and games that are typically associated with the opposite sex

- preferring to play with children of the opposite biological sex

- disliking or refusing to pass urine as other members of their biological sex usually do– for example, a boy may want to sit down to pass urine and a girl may want to stand up

- insisting or hoping that their genitals will change– for example, a boy may say he wants to be rid of his penis, and a girl may want to grow a penis

- feeling extreme distress at the physical changes of puberty

- Children with gender dysphoria may display some, or all, of these behaviours. However, in many cases, behaviours such as these are just apart of childhood and do not necessarily mean that your child has gender dysphoria.

- For example, many girls behave in a way that can be described as “tomboyish”, which is often seen as part of normal female development. It is also not uncommon for boys to role play as girls and to dress up in their mother’s or sister’s clothes. This is usually just a phase.

- Most children who behave in these ways do not have gender dysphoria and are not transgender. Only in rare cases does the behaviour persist into the teenage years and adulthood.

Gender dysphoria in teenagers and adults

- If the feelings of gender dysphoria are still present by the time your child is a teenager or adult, it is likely that they are not just going through a phase.

- If you are a teenager or an adult whose feelings of gender dysphoria begun in childhood, you may now have a much clearer sense of your gender identity and how you want to deal with it.

- The ways that gender dysphoria affects teenagers and adults is different to the way that it affects children.

- If you are a teenager or adult without doubt that your gender identity is at odds with your biological sex

- comfortable only when in the gender role of your preferred gender identity

- a strong desire to hide or be rid of the physical signs of your sex, such as breasts, body hair or muscle definition

- a strong dislike for– and a strong desire to change or be rid of – the genitalia of your biological sex

Without appropriate help and support, some people may try to suppress their feelings and attempt to live the life of their biological sex. Ultimately, however, most people are unable to keep this up.

Having or suppressing these feelings is often very difficult to deal with and, as a result, many trans people and people with gender dysphoria experience depression, self-harm or suicidal thoughts.

See your GP as soon as possible if you have been experiencing feel depressed or suicidal.

See your GP if you think that you or your child may have gender dysphoria. If necessary, they can refer you or your child to a specialist Gender Identity Clinic (GIC).

GICs offer expert support and help, as well assessment and diagnosis, for people with gender dysphoria.

Assessment

A diagnosis of gender dysphoria can usually be made after an in-depth assessment carried out by two or more specialists.

This may require several sessions, carried out a few months apart, and may involve discussions with people you are close to, such as members of your family or your partner.

The assessment will determine whether you have gender dysphoria and what your needs are, which could include:

- whether there is a clear mismatch between your biological sex and gender identity

- whether you have a strong desire to change your physical characteristics as a result of any mismatch

- how you are coping with any difficulties of a possible mismatch

- how your feelings and behaviours have developed over time

- what support you have, such as friends and family

The assessment may also involve a more general assessment of your physical and psychological health.

If the results of the assessment suggest you or your child have gender dysphoria, staff at the GIC will then work with you to come up with an individual treatment plan. This will include any psychological support you may need and a discussion about preliminary timescales for any medical or surgical treatment.

Treatment for gender dysphoria aims to help people with the condition live the way they want to, in their preferred gender identity.

What this means will vary from person to person, and is different for children, young people and adults. Your specialist care team will work with you on a treatment plan that is tailored to your needs.

Guernsey are working towards an updated care pathway which will be similar to that which is use in Jersey. The diagram below explains the process of care, for the full Jersey documentation please visit http://transjersey.org/2014/10/05/pathway-to-care-leaflet/

Treatment for children and young people

If your child is under 18 and thought to have gender dysphoria, they will usually be referred to a specialist child and adolescent Gender Identity Clinic (GIC).

Currently, the only specialist clinic for young people with gender identity issues is run by the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust in London, although they occasionally provide satellite clinics in other parts of the country.

Staff at these clinics can carry out a detailed assessment of your child, to help them determine what support they need. Depending on the results of this assessment, the options for children and young people with suspected gender dysphoria can include:

- family therapy

- individual child psychotherapy

- parental support orcounselling

- group work for young people and their parents

- regular reviews to monitor gender identity development

- hormone therapy (see below)

Your child’s treatment should be arranged with a multi-disciplinary team (MDT). This is a group of different healthcare professionals working together, which may include specialists such as mental health professionals and paediatric endocrinologists (specialists in hormone conditions in children).

Most treatments offered at this stage are psychological, rather than medical or surgical. This is because the majority of children with suspected gender dysphoria do not have the condition once they have reached puberty. Psychological support, therefore, offers young people and their families a chance to discuss their thoughts and receive support to help them cope with the emotional distress of the condition, without rushing into more drastic treatments.

Hormone therapy

If your child has gender dysphoria and they have reached puberty, they could be treated with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. These are synthetic (man-made) hormones that suppress the hormones naturally produced by the body.

Some of the changes that take place during puberty are driven by hormones. For example, the hormone testosterone, which is produced by the testes in boys, helps stimulate penis growth.

As GnRH analogues suppress the hormones that are produced by your child’s body. They also suppress puberty and can help delay potentially distressing physical changes caused by their body becoming even more like that of their biological sex, until they are old enough for the treatment options discussed below.

GnRH analogues will only be considered for your child if assessments have found that they are experiencing clear distress and have a strong desire to live as their gender identity.

Please check the NHS website for the latest guidance on GnRH analogues.

Transition to adult services

When your child reaches 18, their care will usually be transferred to a gender clinic specialising in support and treatment for adults with gender dysphoria.

By this age, doctors can be much more confident in making a diagnosis of gender dysphoria and, if desired, steps can be taken towards more permanent hormone or surgical treatments to alter your child’s body further, to fit with their gender identity.

Treatment for adults

Adults with gender dysphoria should be referred to a specialist adult GIC. As with specialist children and young people GICs, these clinics can offer ongoing assessments, treatments, support and advice, including:

- mental health support, such as counselling

- cross-sex hormone treatment (see below)

- speech and language therapy– to help alter your voice, to sound more typical of your gender identity

- hair removal treatments, particularly facial hair

- peer support groups, to meet other people with gender dysphoria

- relatives’ support groups, for your family

For some people, support and advice from a clinic are all they need to feel comfortable in their gender identity. Others will need more extensive treatment, such as a full transition to the opposite sex. The amount of treatment you have is completely up to you.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy for adults means taking the hormones of your preferred gender:

- a trans man (female to male) will take testosterone (masculinising hormones)

- a trans woman (male to female) will take estrogen, usually in combination with anti-androgens (feminising hormones)

The aim of hormone therapy is to make you more comfortable with yourself, both in terms of physical appearance and how you feel. These hormones start the process of changing your body into one that is more female or more male, depending on your gender identity. They usually need to be taken indefinitely, even if you have gender reassignment surgery.

Hormone therapy may be all the treatment you need to enable you to live with your gender dysphoria. The hormones may improve how you feel and mean that you do not need to start living in your preferred gender or have surgery.

Changes in trans women

If you are a trans woman, changes that you may notice from hormone therapy include:

- your penis and testicles getting smaller

- less muscle

- more fat on your hips

- your breasts becoming lumpy and increasing in size slightly

- less facial and body hair

Hormone therapy will not affect the voice of a trans woman. To make the voice higher, trans women may need voice therapy and, rarely, voice modifying surgery.

Changes in Trans men

- If you are a trans man, changes you may notice from hormone therapy include more body and facial hair

- more muscle

- your clitoris (a small, sensitive part of the female genitals) getting bigger

- your periods stopping

- an increased sex drive (libido)

Your voice may also get slightly deeper, but it may not be as deep as other men’s voices.

RIsks

There is some uncertainty about the possible risks of long-term masculinising and feminising hormone treatment, and you should be made aware of the potential risks and the importance of regular monitoring before treatment begins.

Some of the potential problems most closely associated with hormone therapy include:

- blood clots

- gallstones

- weight gain

- acne

- hair lossfrom the scalp

- sleep apnoea– a condition that causes interrupted breathing during sleep

Hormone therapy will also make both trans men and trans women less fertile. Your specialist should discuss the implications for fertility before starting treatment, and they may talk to you about the option of storing eggs or sperm (known as gamete storage) in case you want to have children in the future. However, this is not available on the NHS.

There is no guarantee that fertility will return to normal if hormones are stopped.

Monitoring

While you are taking these hormones, you will need to have regular check-ups, either at your gender identity clinic or your local GP surgery. You will be assessed, to check for any signs of possible health problems and to find out if the hormone treatment is working.

If you do not think that hormone treatment is working, talk to the healthcare professionals who are treating you. If necessary, you can stop taking the hormones (although some changes are irreversible, such as a deeper voice in trans men and breast growth in trans women)

Alternatively, you may be frustrated with how long hormone therapy takes to produce results, as it will take a few months for some changes to develop. Hormones have the potential to change your bone structure & height if you have not experienced ephyseal closure, which generally occurs around the age of 25.

Hormones for gender dysphoria are also available from other sources, such as the internet, and it may be tempting to get them from here instead of through your clinic. Hormones from other sources are not licensed and therefore not safe. If you decide to use these hormones, let your doctors know so that they can monitor you.

Social gender role transition

If you want to have gender reassignment surgery, you will usually first need to live in your preferred gender identity full time for at least a year. This is known as “social gender role transition” (previously known as “real life experience” or “RLE”) and it will help in confirming whether permanent surgery is the right option.

You can start your social gender role transition as soon as you are ready, after discussing it with your care team, who can offer support throughout the process.

The length of the transition period recommended can vary, but it is usually between one and two years. This will allow enough time for you to have a range of experiences in your preferred gender role, such as holidays and family events.

For some types of surgery, such as a bilateral mastectomy (removal of both breasts) in trans men, you may not need to complete the entire transition period before having the operation.

Surgery

Once you have completed your social gender role transition and you and your care team feels you are ready, you may decide to have surgery to permanently alter your sex.

The most common options are discussed below, but you can talk to members of your team and the surgeon at your consultation about the full range available.

Trans Man Surgery

For trans men, surgery may involve:

- a bilateral mastectomy (removal of both breasts)

- a hysterectomy (removal of the womb)

- a salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries)

- phalloplasty or metoidioplasty (construction of a penis)

- scrotoplasty (construction of a scrotum) and testicular implants

- a penile implant

A phalloplasty uses the existing vaginal tissue and skin taken from the inner forearm or lower abdominal wall to create a penis. A metoidioplasty involves creating a penis from the clitoris, which has been enlarged through hormone therapy.

The aim of this type of surgery is to create a functioning penis, which allows you to pass urine standing up and to retain sexual sensation. You will usually need to have more than one operation to achieve this.

Trans Woman Surgery

For trans women, surgery may involve:

- breast implants

- facial feminisation surgery (surgery to make your face a more feminine shape)

- an orchidectomy (removal of the testes)

- a penectomy (removal of the penis)

- vaginoplasty (construction of a vagina)

- vulvoplasty (construction of the vulva)

- clitoroplasty (construction of a clitoris with sensation)

- There are legal safeguards to protect against discrimination (see guidelines for gender dysphoria), but other types of prejudice may be harder to deal with. If you are feeling anxious or depressed since having your treatment, speak to your GP or a healthcare professional at your clinic.

• Sexual orientation

- Once transition has been completed, it is possible for a trans man or woman to experience a change of sexual orientation. For example, a trans woman who was attracted to women before surgery maybe attracted to men after surgery. However, this varies greatly from person to person, and the sexual orientation of many transsexuals does not change.

- If you are a transsexual going through the process of transition, you may not know what your sexual preference will be until it is complete. However, try not to let this worry you. For many people, the issue of sexual orientation is secondary to the process of transition itself.